Tuesday, 23 July 2013

Monday, 15 April 2013

Review of Fault Lines in Atlanta Journal-Constitution

BY FELICIA FEASTER - FOR THE AJC

British photographer George Georgiou documents a world of dramatic contrasts. In his images old churches are set against the metal cafe tables of an al fresco restaurant. His photographs of modern Turkey juxtapose ancient mountains against Lego-housing blocks the color of Lifesavers — old and spanking new clashing at every turn.As he says in text accompanying his show “Fault Lines/Turkey/East/West” at Jackson Fine Art, “a struggle is taking place between modernity and tradition.” He records the unusual circumstance of Turkey, not only geographically set between Europe and the Middle East, but also spiritually, as it navigates tradition and progress. Georgiou spent five years living in the country and collected his images of Turkey in the book “Fault Lines/Turkey/East/West,” a portion of which are on view at the Buckhead gallery.

In “Hakkari” (2007), a cosmopolitan-looking man in a suit hoses off his building’s balcony, a contemporary hero far above the fray. Below him lies the frantic, timeless pulse of the city’s street life, flanked in the distance by the ever-present mountains that factor into so many of Georgiou’s photographs. You get the sense of one world defined by iPhones and the latest Beyonce track coexisting with a landscape that will outlive this and many other generations.

Urbanity seems like a facade that could be easily swept aside in a dust storm. At a seaside war memorial in “Mersin” (2007), a fighter jet has been defaced with graffiti, and an array of ordinary Turks pass by the monument, caught up in their own realities. There is a desolation in many of these city images — you realize how attuned the Western eye is to advertisements and embellishment and how absent that visual clutter is from these images.

There is very little in the way of decoration or ornamentation in the Turkey Georgiou documents. Even the clean new apartment buildings that have been built to accommodate the rapid influx of villagers into the city are surrounded by dirt roads and newly planted saplings that attest to the rapidity of change here. The way he shoots the landscape is dramatic — the mountains, sky and sea surround the land, giving an impression of something eternal coexisting with the transient.

Photographers are of course drawn to such moments of conflict and paradox. They make for thrillingly alive and rich images. And there is something undeniably arresting, even magical in Georgiou’s images. He certainly understands the power of those sorts of juxtapositions, as when he sets a ramshackle three-wheeled vehicle with a canvas roof flapping against the wind, against a development further down the dirt road of towering housing blocks. It looks like a Terry Gilliam futurescape — some fantastic vision of what could be, though in the case of Turkey, it is also a portrait of what is.

The photographer’s portraits are just as arresting. He captures people on crowded city streets and seen at a low angle, against vast grey sky. With this dramatic perspective, his figures become almost sculptural, like the iconic statuary in a Communist country’s city squares. The people themselves are emblematic of Turkey’s stark contrasts of old and new, East and West. Older men in ill-fitting suits and out-of-date haircuts coexist alongside the international hipster set decked out in the facial hair and red lips of a Benetton ad. But all of that diversity unfolds against a backdrop of silt skies and dirt roads, which gives the whole endeavor the attitude of an old Hollywood Western town on the cusp of some massive change.

Whether in his landscapes or portraits, Georgiou has a way of wrapping his subjects with devouring expanses of space — lots of sky, mountain ranges and long dusty roads that emphasize a feeling of loneliness that weighs heavily in his photographs.

Monday, 4 March 2013

Wednesday, 17 October 2012

Tuesday, 29 May 2012

Tbilisi Photo Festival

I am exhibiting 13 large prints from Turkey in a group show on the Black Sea in Tbilisi,

alongside Vanessa Winship, Rafal Milach, Gueorgui Pinkhassov, Yuri kozyrev, Boris milhailov, Thomas Dworzak and Justyna Mielnikiewicz.

The Tbilisi Photo festival also has a lot of other exhibitions.

| SYRIA: TESTIMONIALS | |

| ON THE ROAD TO CHECHNYA Stanley Green | |

| THE COLOURS OF THE BLACK SEA | |

| IRAN: THE UNVEILED IMAGE | |

| CAUCASUS: NINETEENTH - CENTURY PORTRAITS | |

| GEORGIAN ABC BOOK |

Tuesday, 27 March 2012

Yeni Yol. A commission for the "Time in Turkey" book.

George Georgiou from Türkiye'de Zaman/Time in Turkey on Vimeo.

Last Summer I was commissioned by Zaman newspaper in Turkey to take part in a book project to celebrate their 25th year. They invited 25 photographers to spend a week photographing Turkey.

The whole project can be seen on the Zaman "Time in Turkey" page.

For this work, I chose the idea of following up on “Fault Lines” by making a road trip on the New Roads. The title in Turkish, “Yeni Yol,” has multiple meanings: New Way, New Aim or New Ideology. From my experience of Turkey, I use the New Roads as a metaphor of the change that is taking place and question what that vision is.

Saturday, 22 October 2011

Hereford Photography Festival

Time & Motion Studies: New documentary photography beyond the decisive moment

Curated by Simon Bainbridge

Saturday 22nd October – Saturday 26th November

Tuesday to Friday 10am – 5pm; Saturday 10am – 4pm

Hereford Museum & Art Gallery, Broad Street, Hereford, HR4 9AU

Time & Motion Studies presents the works of five photographers, each the result of deliberate and sustained observation. But more than that, each employs a carefully thought-out strategy for their study, a methodology by which to transcribe and communicate ideas about the world, tackling subjects that aren’t always obviously photogenic. For the photographers in the exhibition, the ideas they are trying to communicate take prescience over aesthetic concerns, although these remain important, both in terms of engaging viewers and in contributing to the development of a wider photographic language.

The festival gives me an opportunity to show these works, five excellent examples of the diversity of contemporary documentary practice, and all of which have appeared inBritish Journal of Photograph, some in the recent past, which I hope the photography crowd will enjoy seeing in the flesh, some of it exhibited for the first time anywhere. But the festival attracts a wider public than just the photography crowd, particularly at the Hereford Museum & Art Gallery, and for these visitors I hope to give a flavour of what photography can be and what it can say, beyond the traditional idea of the artist photographer as someone wandering the earth communing with nature. And by showing five very different approaches, I hope to expose the photographers behind the images, to get viewers thinking about how they position themselves – both physically, embedding themselves into situations, and in terms of negotiating themselves into spaces – to make their pictures.

In the case of Donald Weber, that’s a very uncomfortable space. Having befriended a Ukrainian policeman whose career was on the rise, he spent years negotiating access to the interrogation room the officer spent much of his time, gaining confessions from mostly petty criminals. Waiting for the moment of confession, the results are a terrifying insight into the justice system, but also, a defining point of departure for the subjects – a cathartic experience sometimes – after which life may never be the same again.

Robbie Cooper exemplifies the increasing convergence between still and moving images, using the first digital camera that truly delivers both, in high resolution. Technology is also at the heart of his subject matter, which is concerned with how our identities are becoming wrapped up in new virtual territories – in this case, capturing animated faces close up through as his subjects engage with computer games and other screen-based worlds. Manuel Vasquez also touches on technology, particularly surveillance culture, in his montages that splice together different moments in time. Captured in largely anonymous public places, they capture the anxiety as well as a sense of spectacle within the spotlight of this constant observation.

George Georgiou is also working with sequential imagery. He is interested in the continued influence Russia plays on its former Soviet neighbours, and how this is manifested in the daily lives of ordinary people, capturing them in sequences shot from the same vantage point. His installation at this year’s festival is his most ambitious realisation of this approach, and is the first time he has presented a work on such a scale. His partner and travelling companion Vanessa Winship takes an altogether different approach. Where as Georgiou remains largely hidden to his subjects, she places her camera in such a way as to invite her subjects to present themselves. She seeks a direct connection, and somehow manages to capture the complexity of this dialogue in the directness and vulnerability of their gazes. Putting them together in the same show, I aim to demonstrate that a photograph is not so much the result of what’s in front of the camera, rather than the motives, instincts and ideas of the person behind it.

Time & Motion Studies also refers to this year’s festival theme of motion, a concept I struggled with at first (after all, photography is all about distilling moments into single frames), until I thought about this idea of the photographer waiting, quiet and still, capturing what before his or her camera. It also got me thinking about one of the most enduring concepts in photography, now nearly 60 years old – “The Decisive Moment”, as termed by Henri Cartier-Bresson. In it’s most simple form, the idea was that every image of a “stolen moment” had it’s own decisive moment, a split-second capture in which “simultaneously and instantaneously the recognition of a fact and the rigorous organisation of visually perceived forms [expressed and signified] that fact”.

It’s not a very fashionable concept anymore (especially when you think about the Becher School photographers who have dominated in the past 25 years, with their monumental images, largely of scenes that denote no single important moment of time). But a sense of the right moment pervades in photography nonetheless, along with photography’s pictorial visual language. Cooper has to decide where to pull the stills from his motion, Weber looks for a moment of confession, and even Georgiou, who presents multiple takes on a time and place, edits from hundreds more moments.

The Decisive Moment was a product of a particular time, when newspapers and magazines were the primary outlet for photographers’ work, a medium through which they could speak to hundreds of thousands of readers. And up until relatively recently that remained the case for anyone with documentary concerns; photographers making their names on smaller titles before hopefully working their way up to bigger commissions on bigger and more prestigious publications.

But there are no big commissions these days, and few photographers can earn a proper living making interesting work for newspapers and magazines anymore. There simply isn’t the budget; a situation that would seem to point to more straightened times, were it for the fact that they are still prepared to pay huge sums for images of celebrity. You can blame it on dumbing down, or the deep conservatism of publishers, or the internet, which has helped drive down the price of professional photography to unsustainable levels through the digital distribution of cheap images.

For photographers the end of print is a reality, at least regards to newspapers and magazines. (On the festival’s opening weekend, Self Publish Be Happy will present a flourishing counter-trend, showcasing the work of independent book publishers who still find vital express in printed matter.) But these publications never really gave them real freedoms to express their points of view, and in their absence, photographers are searching for news ways to communicate with audiences, free from the editorial confines of newspaper dictat.

Although they operate in uncertain times, these five photographers present us with clear and articulate takes on the world. And if such different voices and approaches can sit side-by-side so easily, isn’t that a sign that photography is maturing, rather than a medium in peril?

Simon Bainbridge

Vanessa Winship: Georgia, 2009-10

Donald Weber Interrogations: Big Zone, Small Zone

Manuel Vasquez: Traces

Robbie Cooper Immersion

George Georgiou The Shadow of The Bear, 2009-10

George Georgiou The Shadow of The Bear, 2009-10: installation detail

Wednesday, 12 October 2011

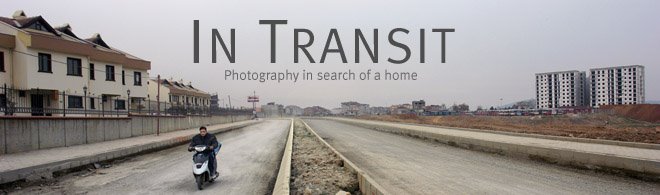

New Blog site for the next year

I will not be posting very often on this blog site over the next year as I will be going a new blog with Vanessa on our travels through the USA.

We are going to attempt to keep a daily stream of posts of our encounters, through text, photos and video.

A brief intro to the blog below and the link

The title for the blog came from an

email conversion I had with a friend as we were preparing for this

extended project into the USA.

ME: So I try to prepare for this big trip to the States, it seems like a strange thing to be doing now...

I have a huge wall map to make it feel more physical ..but I don't have a free wall to put it on so I must grapple with it on my desk, I'm partly trying not to spoil it, but at the same time I want to spread it out on the floor and tread on it and get it over with...

C: I understand, it is a weird feeling for you to prepare your travel, a big movement when everything already moves around.

I like so much the way you talk about your huge wall map. Do you know this expression "The map is not the territory" ?

The father of general semantics, Alford Korzybski stated, "A map is not the territory it represents, but if correct, it has a similar structure to the territory, which accounts for its usefulness". What this means is that our perception of reality is not reality itself but our own version of it, or our "map".

No two people can have exactly the same map.

So here we are, 2 photographers, 1 car, same journey, 2 visions.

Monday, 10 October 2011

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)