By ADAM STOLTMAN NYT Lens Blog

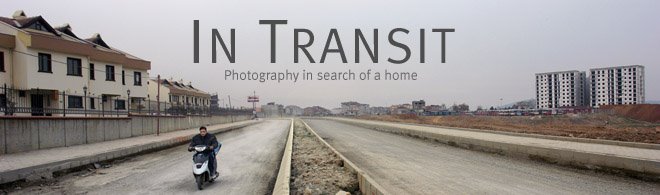

Through a series of haunting architectural and landscape scenes of Turkey’s rush toward modernization — and the resulting tension between the secular and the modern — George Georgiou

has visually put his finger on a kind of listless alienation which at times can seem to pervade globalized society. Turkey, traditionally a bridge between East and West, seemed a logical choice for such a cautionary vision.

His latest book, “Fault Lines: Turkey From East to West” (Schilt Publishing), forces us to consider not so much the emotions that connect us, but rather the spaces that separate us.

A soft-spoken photojournalist best known for searing black-and-white pictures from Kosovo and Serbia, Mr. Georgiou was always curious about Turkey, given its traditional rivalry with and closeness to the countries of his heritage, Greece and Cyprus. His visit in 2003 coincided with the terrorist bombings of a synagogue and of the British Consulate. They sparked a desire to go deeper in his understanding of the country. He spent the next five years living and working there.

The results of his explorations were far different than he expected. “My black-and-white work in Kosovo was more emotional and personal,” he said. “This required a contrast of styles to something landscape driven, and relatively devoid of people.”

Trying to capture this “alienating landscape,” Mr. Georgiou was drawn to small groups of people interacting — and not interacting — within and against these artificial constructs. It was a visual metaphor for what can be the homogenizing and disrupting effects of globalization.

“I was fascinated by how this sort of swamps all of us, and everyone is lost in their own heads,” he said.

Little by little, the book began to take shape and find its own visual language. “I am drawn to the space we find ourselves in generally as human beings” amid so much change, he said. “The imposition of an urban landscape that has been put upon this mostly rural landscape in Turkey with its hard mountains, 1,000 to 2,000 meters above sea level, allowed me to explore this.”

In spite of the horrors he has covered and the foreboding quality of many of his images, Mr. Georgiou describes himself as a “strangely optimistic” person.

“I don’t believe that we are all going to end up the same because of globalization,” he said. “When I am in the States, it still feels like the States as opposed to Europe, which still feels like Europe. In general we are always making our lives better with each generation.”

As if to underscore this optimism, the book ends on a refreshingly hopeful note. After pages of bleak urban landscapes, the last few pages are devoted to a series of portraits of young people shot against blue sky. To the photographer, these images of youth — pictured as they walk through Taksim Square, the modern heart of Istanbul — seem to reject much of what has come before, and speak to the power of individuals to create their own destinies. “It is as if they are each saying, ‘We will not allow ourselves to be defined by others.’”

No comments:

Post a Comment